Hasta Carmen

series of 12 digital images, commission for Cordite Review, 2021

When I met the co-leaders of San Marino at the Olympics, I knew where it was because of Carmen Sandiego.

–President Bill Clinton, The New York Times, 1996

We just don’t know the geopolitics of Carmen Sandiego, and in some sense, it’s really important to find out. What did the game include about history? More importantly, given the brevity of the information presented, what did it exclude? Were there outright falsehoods in these games or racial, ethnic, or gender biases? We don’t know the answers to any of these questions.

–Alexis C Madrigal, ‘The Geopolitics of Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?’, The Atlantic, 2011

Games come to signify not just code, but interaction with a certain kind of machine, space, and time.

–Rhiannon Bettivia, ‘Where Does Significance Lie: Locating the Significant Properties of Video Games in Preserving Virtual Worlds II Data’, International Journal of Digital Curation, 2016

I’ve always loved the video game Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego. First released in 1985, it spawned the edu-tainment software revolution of the 90s, which I was very much caught up in. While the Carmen universe has expanded to include live-action and cartoon TV series, books, and multiple versions of the video game focused on history and specific geographic areas, the original Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego game was a world geography challenge. With Carmen as the brilliant antagonist and leader of a crime organisation known as VILE, players would track her and her cronies around the world in an attempt to thwart their brazen attempts at stealing famous monuments and items of cultural heritage. Ostensibly made for children in the United States, the game positions the player as a gumshoe ACME agent (a quasi-CIA operation) on the hunt for Carmen, a hispanic-coded criminal – though, interestingly, Carmen is largely positioned as non-threatening to the player.

At the time I was playing Carmen in my youth, I was also beginning to fully comprehend my Chilean cultural background. From Australia, I absorbed any Chilean references that came my way, trying to piece together an understanding of my cultural identity without being present in the country itself. How strange to look back on this now, thinking of myself as the daughter of a Chilean exile who fought against the CIA backed Pinochet dictatorship, play-acting the role of a United States agent.

When considering the individual players themselves, the geopolitics of Carmen is incredibly complex. The selected locations are often presented as exotic or other-ised to the United States and displayed within the context of a criminal investigation. This US-centrism also plays out in other ways, as Marsha Kinder infers of the 90s TV cartoon version in Media Wars in Children’s Electronic Culture: ‘The red coding [of Carmen’s outfit] also evokes Carmen’s past as a former spy who speaks flawless Russian and who got her hardware from the Soviet Union – a backstory that helps recuperate the cold-war paradigm.’

Carmen played a huge role in geography education for generations of children. While the game developers preferred to see the games as exploration rather than education, it is clear that the game’s success was deeply rooted in its positive reception within schools and its marketing as classroom-based software. The games did develop over time, with the country facts changing due to shifting geopolitics. However, what is learned from these games is not solely contained within the borders of code but permeates into the physical social experience of gameplay, the temporal contexts, and the relationships of individual players with the content presented. Using my personal experience as a conduit, in Hasta Carmen I attempt to interrogate the information learned from a political and sociological viewpoint – looking at how the positioning of a specific country within the game merges with the lived experience of the player over time.

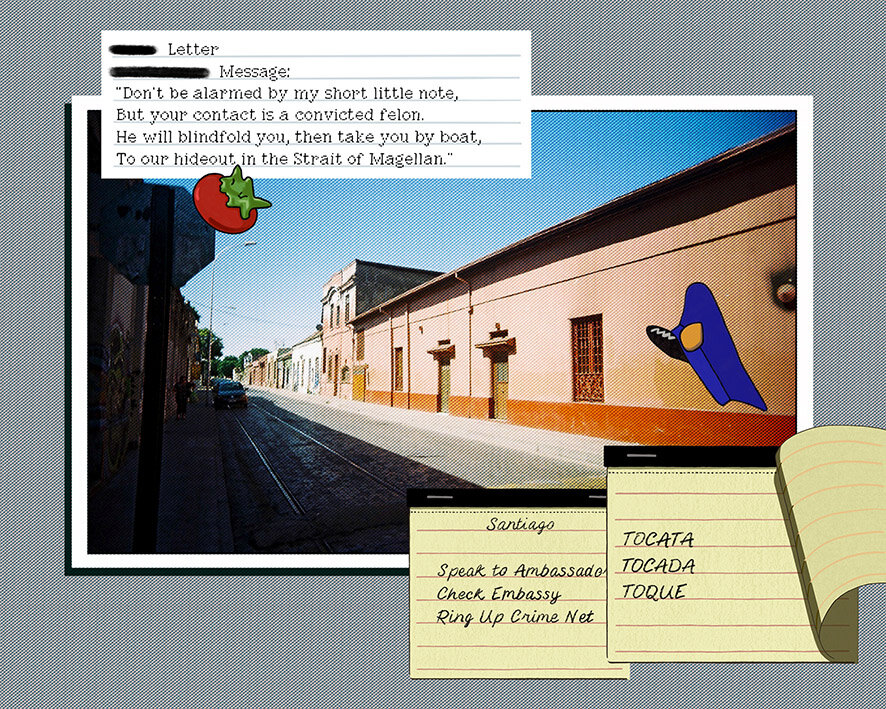

In Hasta Carmen I use the visual lexicon of these early games (specifically Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? classic and deluxe editions), redrawing and playing with elements of the graphical interface. Collated clues, to-do lists and country information specific to Chile from within the game are mixed with notes and photography from my first trips to Chile in re-drawn gameplay fonts and framing. These two sets of information come from very different sources and perspectives. However, they combine to acknowledge the complex web in which we construct understandings of cultural identity.

Both my experience of Chile and the gameplay of Carmen are focused on investigations (as is much of my art practice). In working on this project, I began to wonder if my experience of playing Carmen also influenced the way I process information. Marsha Kinder further suggests that ‘… since these young viewers are still undergoing a process of cognitive development, which helps establish the basic schemata by which they organize perceptual data, that very infrastructure can potentially be inflected by the structure of the particular medium they are monitoring.’

Regardless, the clues have brought me here and I will continue my sleuthing. As the Spanish say, ‘Hasta la vista, ta ta for now, Hon.’

Text and images originally commissioned by Cordite Review.